Antheraea pernyi (Guérin-Méneville)

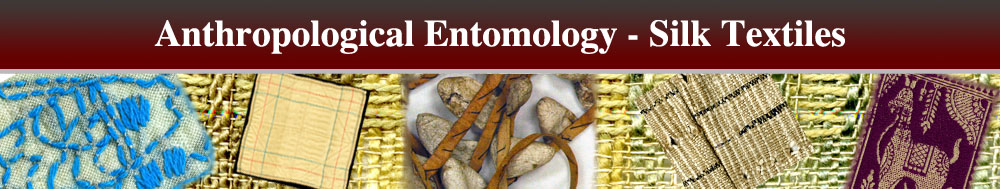

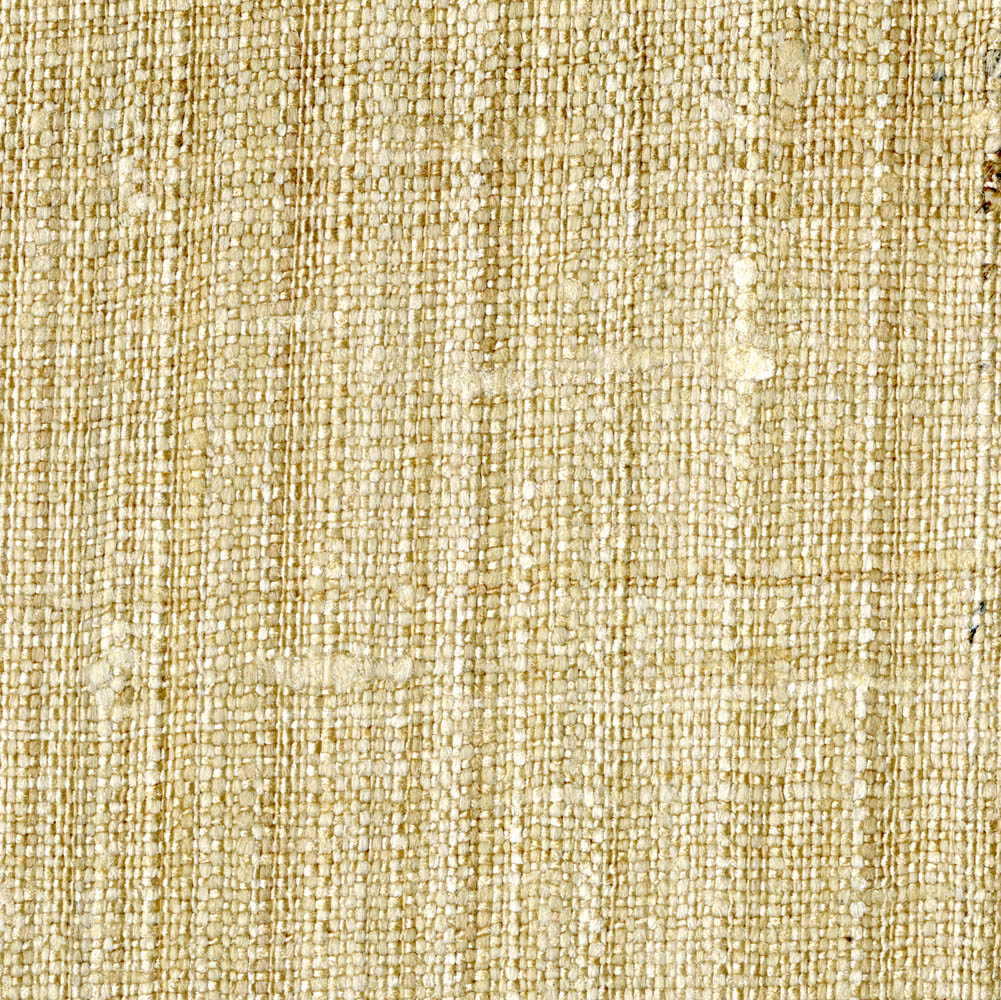

Tussah Silk

This is the best-known and most widely used of all the wild silks. It is derived from Antheraea pernyi (Guérin-Méneville), grown outdoors on oak trees in China for more than two millennia (Chen 2012, Chou 1990, Liu et al. 2010). The natural color of the silk is a pinkish beige. Tussah is primarily grown in the Northeast, in the provinces of Shandong, Liaoning, and Hebei. It was introduced into Japan in 1877 where it was cultivated locally on a small scale into the 20th century. Tussah silk is also raised in both Koreas. Some tussah silk was called pongee and Shantung in the United States and United Kingdom during the first half of the 20th century, but those names have also been applied to types of mulberry silk. Some of the famous “mission embroidery” pieces imported from China in the 1920s are made of tussah silk (Watson 1996).

The book cited here as SRIL (1994) is a comprehensive reference that provides detailed text and color figures of larvae, cocoons, and adults of over 130 named varieties (strains) of A. pernyi. The caterpillars are normally green, but some strains have yellow, blue, and even orange larvae. The cocoons are normally beige, but some strains with white silk have been developed at the Sericulture Research Institute of Liaoning in Fengcheng. Other important research centers for tussah are in Shenyang and Dandong, the latter city on the Yalu River across from North Korea. Because it is so easy to rear, Antheraea pernyi has been used in laboratories around the world to study diapause, endocrinology, and other aspects of insect physiology. Antheraea pernyi was derived by artificial selection at least 2000 years ago in northeastern China, from the Himalayan A. roylei (Peigler 2012).

Many articles of clothing in the West contain tussah silk. The reeled silk has a smooth sheen like domestic silk, but the rougher spun silk was highly favored by designers of high-end fashion to make women’s and men’s suits, blazers, dresses, shirts, scarves, and other garments and accessories. However, this trend has declined since the 1990s, because China began to sell most of its unfinished tussah silk (as cocoons, yarns, threads, and floss) to India, to be used as a substitute for the over-exploited tropical tasar. Sometimes tussah is blended with cotton or synthetic fibers. Tussah silk floss is also used in quilting to make duvets. Tussah is popular with Americans who have spinning wheels, and many women knit or crochet sweaters and scarves with tussah yarn. Tussah fabrics are still obtainable on the internet from retail sellers in the United States who import cloth from China, but some vendors carelessly use the word tussah to refer to some coarse forms of mulberry silk.

References

Chen, F.-L. 2012. Tussah outdoor rearing technique. Golden Shield Publisher, Beijing.

124 pp. [in Chinese]

Chou, I. 1990. A history of Chinese entomology. (Translated by Siming Wang.) Tianze Press,

Xian. 248 pp., 32 color plates.

Liu, Y.-Q., Y.-P. Li, X.-S Li & L. Qin. 2010. The origin and dispersal of the domesticated

Chinese oak silkworm, Antheraea pernyi, in China: a reconstruction based on ancient texts.

Journal of Insect Science 10(180): 1-10.

Peigler, R. S. 2012. Diverse evidence that Antheraea pernyi (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) is

entirely of sericultural origin. Tropical Lepidoptera Research 22(2): 93-99. PDF

SRIL. 1994. [Editorial team at Sericultural Research Institute of Liaoning.] The records of

tussah varieties in China. Liaoning Science Technology Publishing House, Shenyang.

6 + 274 pp. [in Chinese]

Qin, Li, editor. 2011. Tussah silkworm science. Beijing Normal University Publishing

Group, Beijing. 317 pp., 24 color plates. [in Chinese]

Watson, S. R. 1996. Missionary embroidery in China. PieceWork 2(2): 49-50.