Samia ricini

Eri Silk

Eri silk, also called endi silk, is second only to Chinese tussah in world production of wild silks. The silkworms and silkmoths are entirely domesticated, and do not exist in nature. The eri silkmoth is Samia ricini (Wm. Jones) (see Peigler & Calhoun 2013), and it was derived hundreds (or more likely, thousands) of years ago in Northeast India from Samia canningi (Hutton). Eri silk has been confounded in some literature with silks of Samia cynthia (Drury) from northeastern China (Chou 1990) and Samia pryeri (Butler) from Japan, but these latter two have only been used on small scales historically. Samia cynthia is the well-known ailanthus silkmoth that was introduced to Europe in the 1850s and to the United States in 1861, but it is now virtually extinct in the United States (Peigler & Naumann 2003).

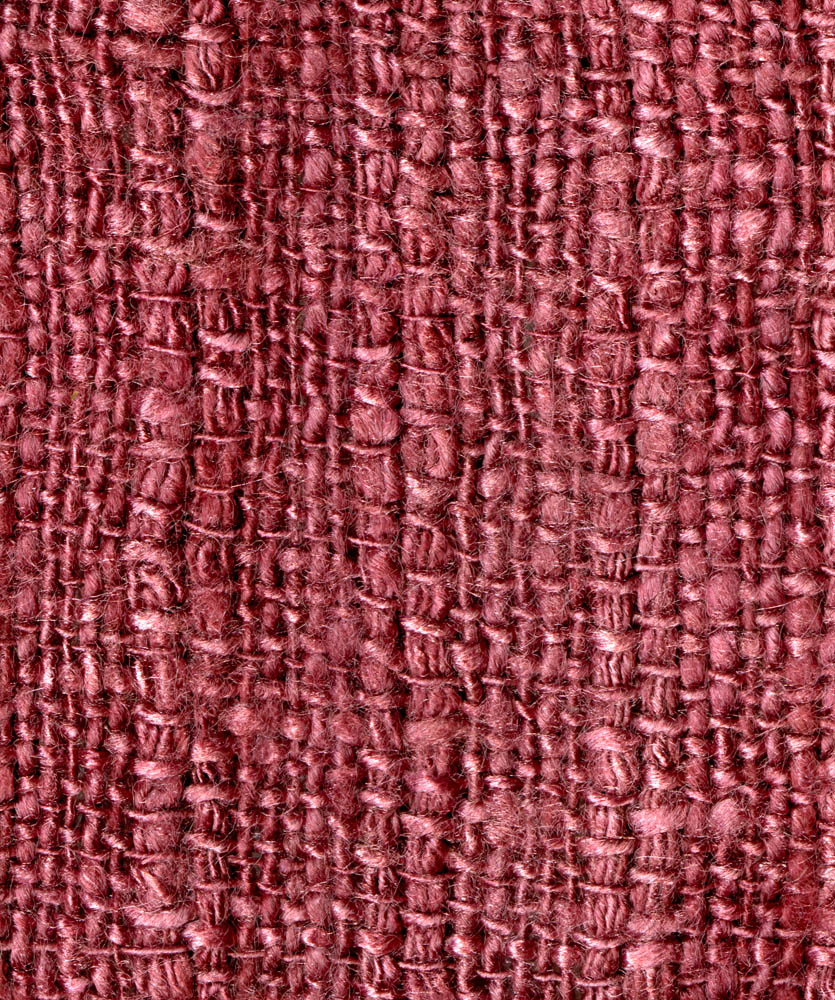

Eri silkworms feed mainly on castor bean leaves (Ricinus communis), but they are reared on several other kinds of plant. The cocoons are large and puffy and contain a lot of silk. The moths do not fly, a result of centuries of domestication like we see for Bombyx mori. Most ericulture is in Northeast India, especially Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Nagaland, and Odisha (Chowdhury 1982), but smaller operations are found all over India (CSB 2006). Ericulture is also well established in Thailand, Vietnam, southern China, and Brazil. Peigler and Naumann (2003) provided a detailed account of ericulture around the world, both historically and recent times. Japanese entrepreneurs introduced ericulture to Ethiopia in 2001 where it has become a successful cottage industry. Ethiopians have long been skilled at spinning and weaving cotton, and eri silk and textiles look and feel like cotton (Javali 2012).

Textile collectors in the West may be familiar with the colorful and intricate weavings of Bhutan (Myers & Bean 1994). Eri silk has long been favored by Bhutanese, and vintage or antique pieces stated to be “wild silk” and “raw silk” are composed of eri silk. Researchers at Khon Kaen University in northeastern Thailand have perfected a method of reeling eri silk from the cocoons, and the fabrics they produce have a nice smooth feel and are more glossy than the spun textiles. Buddhist monks in Tibet, Bhutan, and Nepal often wear wrappers made of eri silk, and the lower classes and Tribal Peoples of Assam and Meghalaya commonly use eri silk for clothing and bedding. It has traditionally been too heavy to be used to make saris, but is perfect for the chilly climate in the Himalayan foothills. Scarves and shawls that are all or partly composed of eri silk are available from internet suppliers (Badola & Peigler 2013). There is a new Japanese technology being employed in Assam called silk sliver (pronounced sly-vur) that yields very fine threads, and this silk sliver is now used to make beautiful sarees (Zethner et al. 2012).

Eri silk is frequently stated to be ahimsa silk (peace silk), with the claim that the moths are allowed to emerge and fly into the forest before the cocoons are used. Eri silkmoths only exist in captivity, and they cannot fly. It is true that the cocoons can be used after the moths emerge, because the silk cannot be reeled like those of mulberry silkworms and the various Antheraea (tussar, tasar, muga, tensan). However, the Tribals of Northeast India who raise eri silkworms eat the pupae before processing the cocoons. Where ericulture exists on larger scales, the pupae are extracted and used to feed poultry, swine, etc., or the oil is extracted (Chowdhury 1982, Singh & Saratchandra 2012, Sharma & Ganguly 2011). In no ericulture operations, large or small, are the moths allowed to emerge, except a small percentage needed to provide eggs for the next rearings. We view the use of terms like non-violent and cruelty-free as a marketing strategy to increases sales, especially on the internet. However, there are cases (Gonometa in Africa and some tropical tasar projects in India) where “peace silk” is valid and supports the moth populations as a renewable resource.

References

Badola, K. & R. S. Peigler. 2013. Eri silk: cocoon to cloth. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh,

Dehra Dun. 93 pp.

Chou, I. 1990. A history of Chinese entomology. (Translated by Siming Wang.) Tianze Press,

Xian. 248 pp., 32 color plates.

Chowdhury, S. N. 1982. Eri silk industry. Directorate of Sericulture & Weaving, Gauhati,

Assam. iii + 177 pp., + 28 figures.

CSB [Central Silk Board]. 2006. Vanya: wild silks of India, vol. 1: an introduction to vanya

silks. Central Silk Board, Bangalore. 196 pp.

Javali, U. 2012. Eri silk: fibre, yarn and fabric characterization. Lambert Academic Publishing,

Saarbrücken. 229 pp.

Myers, D. K. & S. S. Bean, editors. 1994. From the land of the thunder dragon: textile

arts of Bhutan. Serindia Publications, London, and Peabody Essex Museum, Salem,

Massachusetts. 247 pp.

Peigler, R. S. & J. V. Calhoun. 2013. Correct authorship of the name Phalaena ricini and the

nomenclatural status of the name Saturnia canningi (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Tropical

Lepidoptera Research 23(1): 39-43. PDF

Peigler, R. S. & S. Naumann. 2003. A revision of the silkmoth genus Samia. University

of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio. 230 pp, 10 maps, 228 figs. (148 in color).

Sharma, M. & M. Ganguly. 2011. Attacus ricini (eri) pupae oil as an alternative feedstock for

the production of biofuel. International Journal of Chemical and Environmental Engineering

2(2): 124-125.

Singh, R. N. & B. Saratchandra. 2012. Eri culture. A.P.H. Publishing Corp., New Delhi.

221 pp.

Wardle, T. 1881. Handbook of the collection illustrative of the wild silks of India, in the

Indian section of the South Kensington Museum, with a catalogue of the collection and

numerous illustrations. Facsimile reprint 2007. Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, Montana.

xii + 163 pp.

Zethner, O., R. Koustrup & D. Barooah. 2012. Indian ways of silk: precious threads bridging

India’s past, present and future. Bhabani Print & Publications, Guwahati, Assam. 128 pp.