Subfamily FORMICINAE Tawny crazy ant (also has been called the hairy crazy ant, Caribbean crazy ant and Rasberry crazy ant) Author: Joe A. MacGown |

||

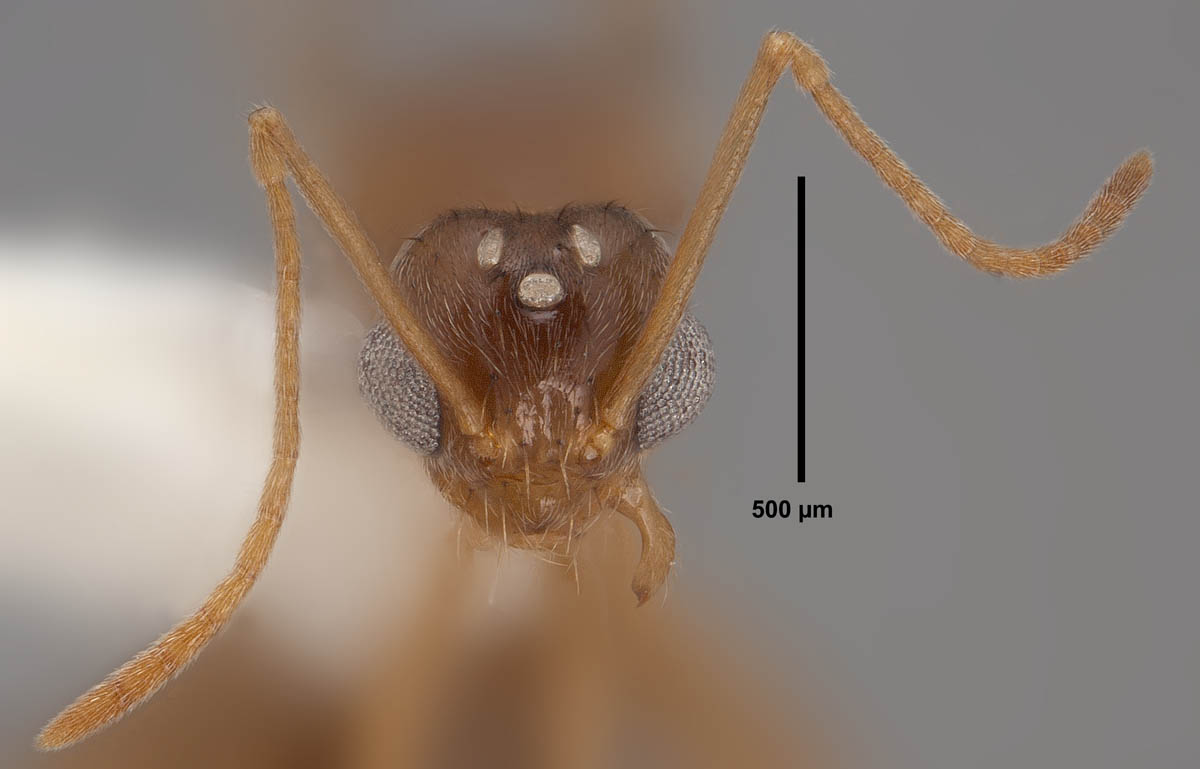

Nylanderia fulva, full face view of a worker (TX) (photo by Joe A. MacGown ) |

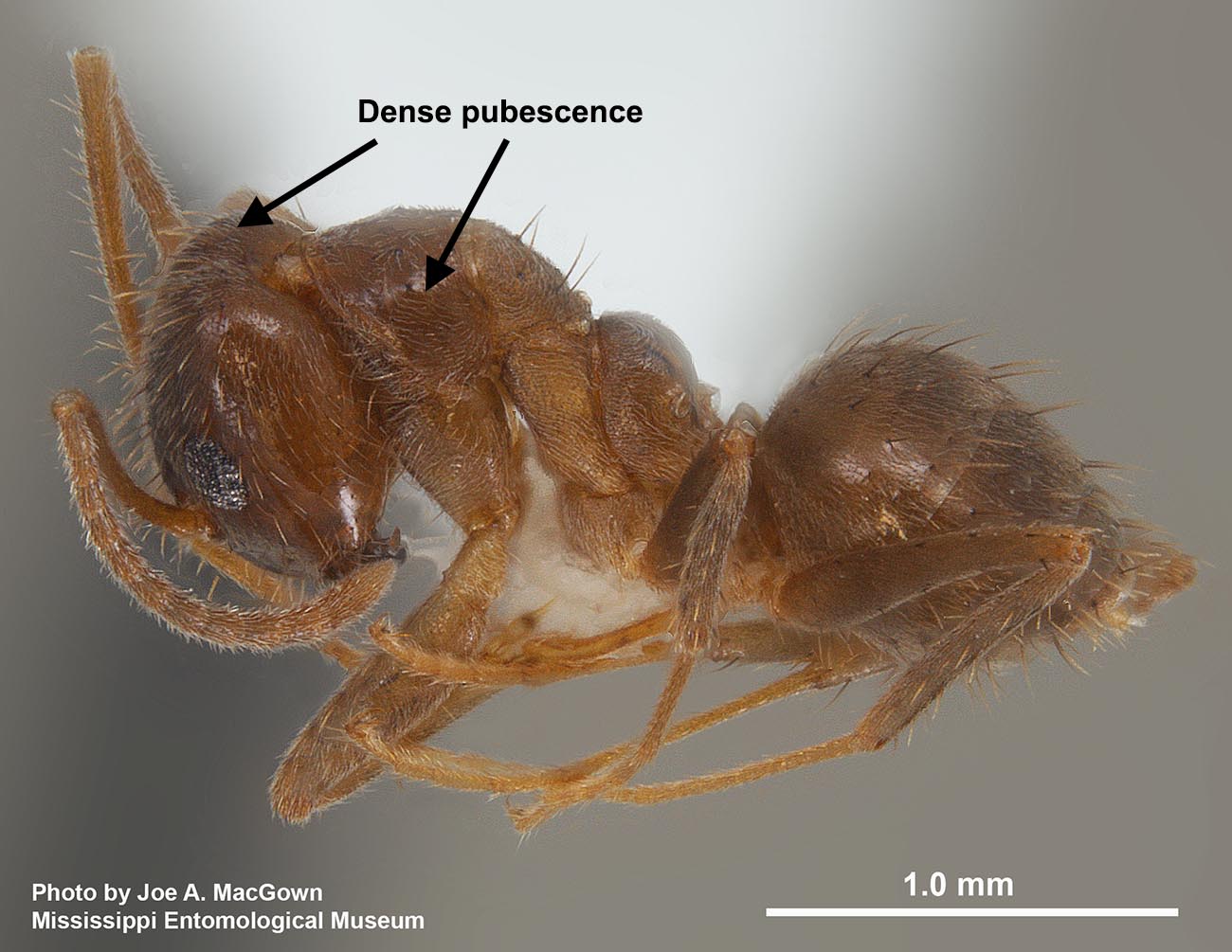

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a worker (TX) (photo by Joe A. MacGown ) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a worker (TX) (photo by Joe A. MacGown ) |

Nylanderia fulva, dorsal view of a worker (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, full face view of a dealate female (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a dealate female (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, full face view of a dealate female (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a dealate female (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, dorsal view of a dealate female (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, full face view of a male (TX, Harris Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a male (TX, Harris Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, dorsal view of a male (TX, Harris Co.) (photo by Ryan Whitehouse & Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, full face view of a male (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a male (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of a male(MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, lateral view of male paramere (note the irregular lengths and placement of setae) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Nylanderia pubens, lateral view of male paramere (note the regular lengths and fanlike placement of setae) (Photo from AntWeb) |

|

Nylanderia fulva workers with brood (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Blake Layton) |

Nylanderia fulva workers foraging (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Blake Layton) |

Nylanderia fulva workers on arm (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Blake Layton) |

Nylanderia fulva workers tending membracids on Ambrosia artimisiifolia (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Blake Layton) |

Nylanderia fulva workers with brood (MS, Hancock Co.) (photo by Blake Layton) |

Trash bag full of dead crazy ants from an area less than a square meter (MS, Jackson Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

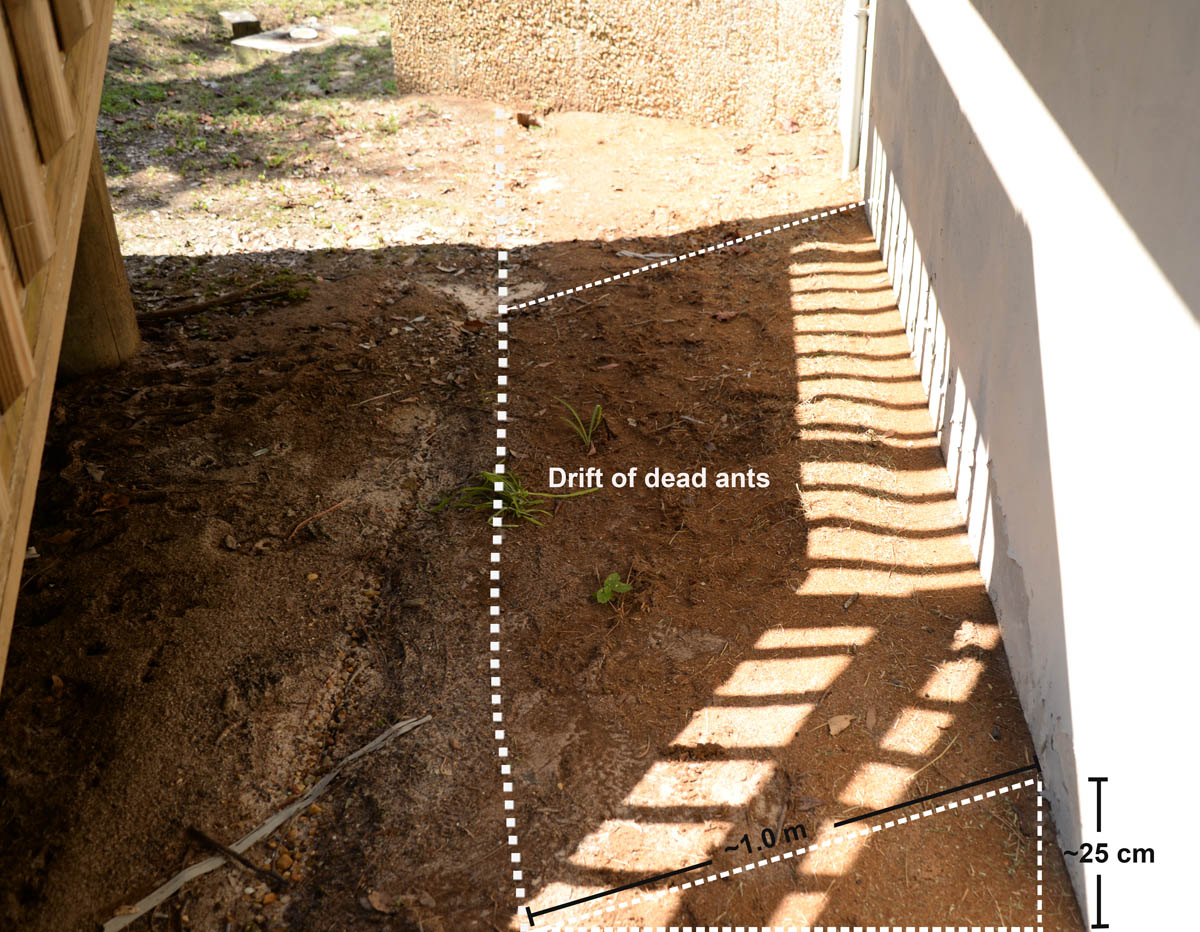

"Drift" (pile) of dead crazy ants against the wall of a building (MS, Jackson Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Standing in a pile of dead crazy ants (MS, Jackson Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

Drift of dead ants with garden trowel (MS, Jackson Co.) (photo by Joe A. MacGown) |

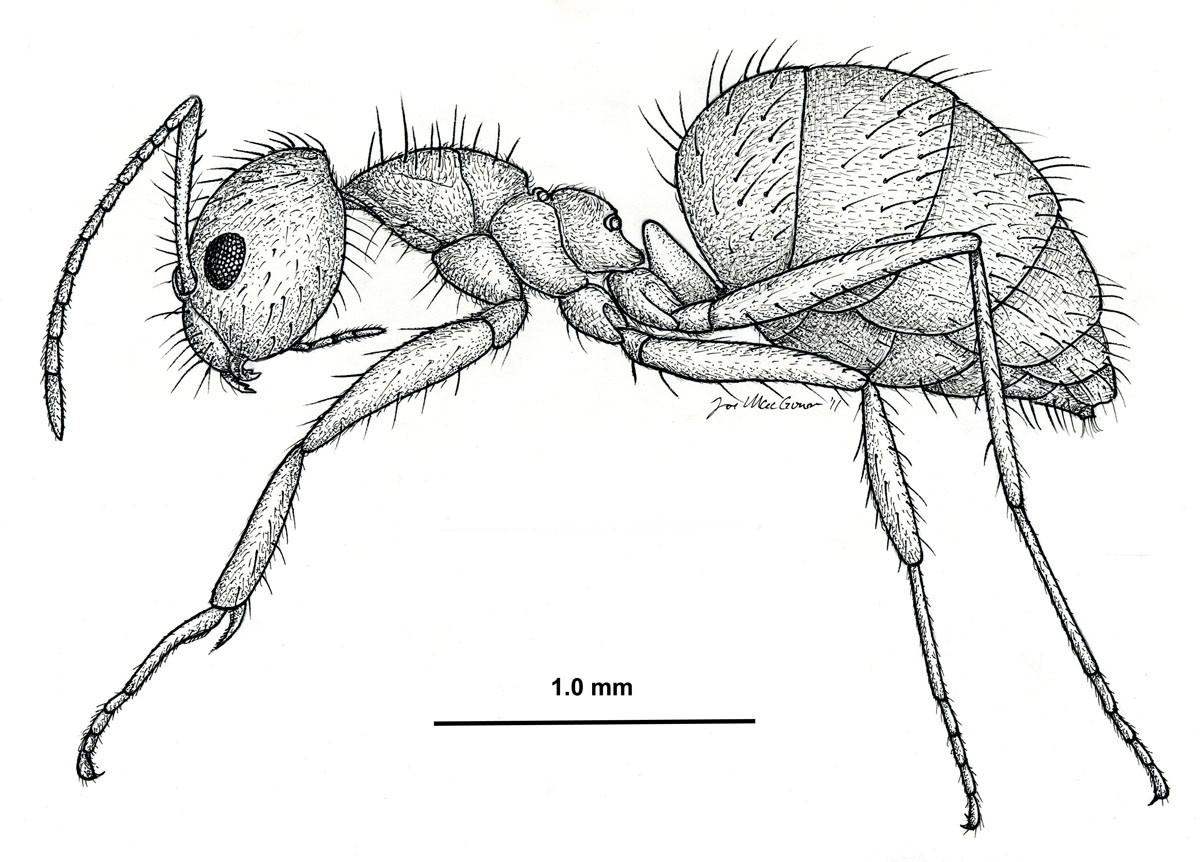

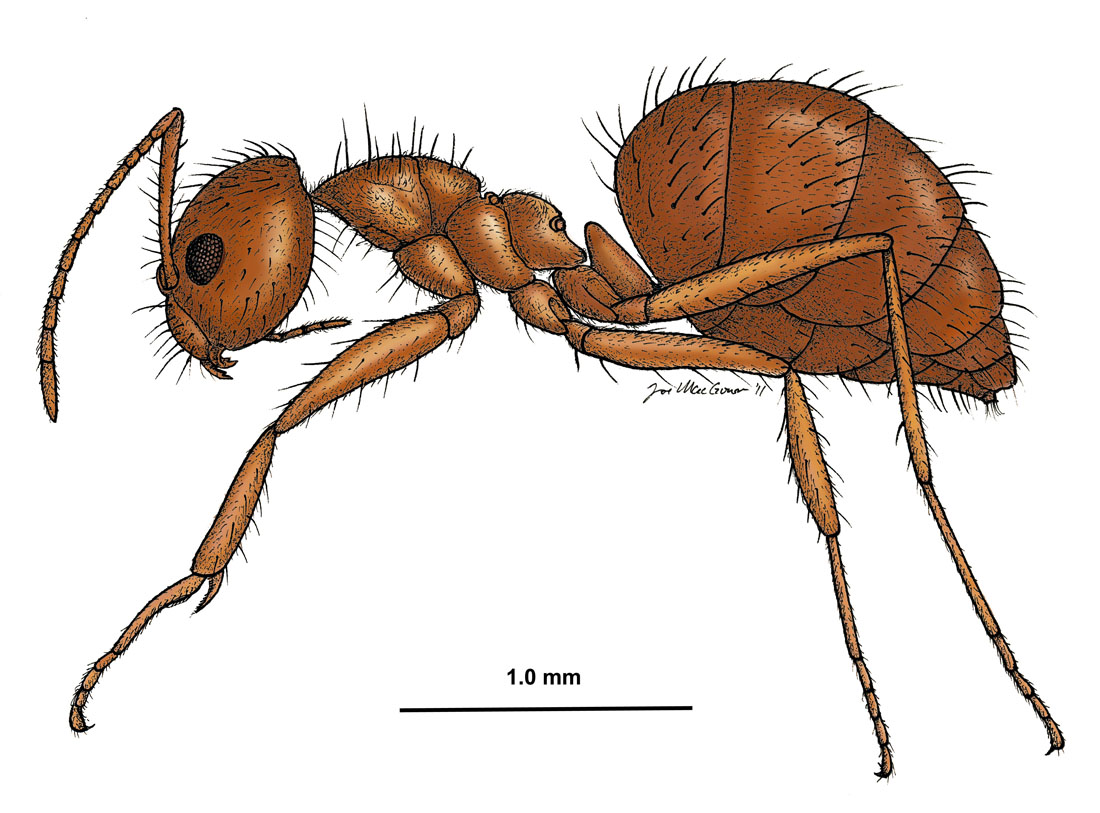

Nylanderia fulva, side view of a worker (drawing by Joe MacGown) |

Nylanderia fulva, side view of a worker (drawing by Joe MacGown) |

|

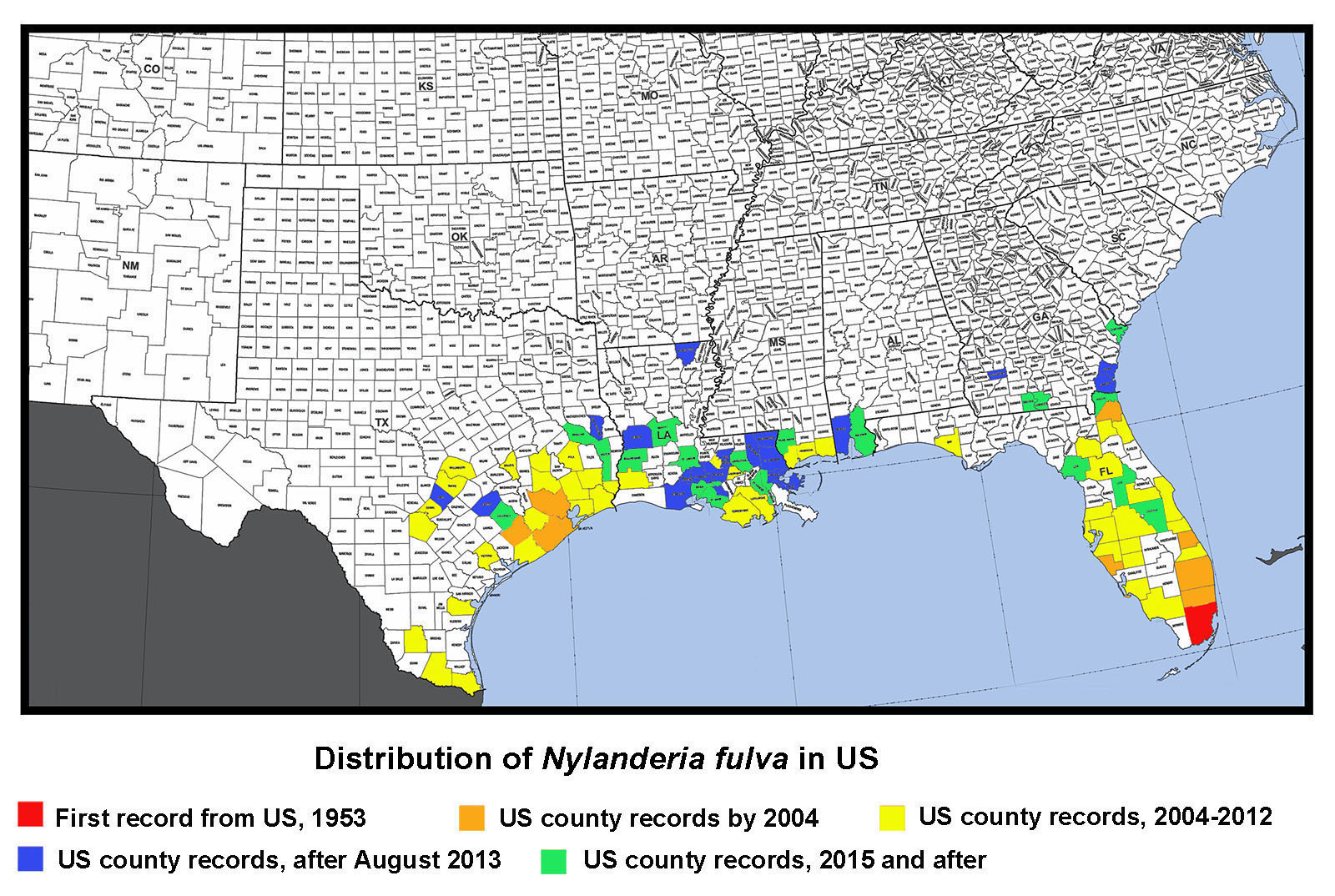

Introduction/History History in the US: The name of this species has been a constant source of confusion since large populations started showing up in Florida in the 1990's (Klotz et al. 1995). Florida specimens were identified as N. pubens based on earlier records of N. pubens reported from Florida 60+ years earlier (Trager, 1984). It is likely that N. pubens was present in Florida historically, but that subsequently N. fulva was introduced and became the dominant species. If so, this would explain why N. pubens has not been commonly found in Florida in recent years. In the US, Nylanderia pubens is likely restricted to southern FL. In the US, Nylanderia pubens sensu stricta is likely restricted to southern Florida. When this ant was found in large numbers in Texas in 2002 (Meyer, 2008), researchers were hesitant to identify it as N. pubens or N. fulva, because of some minor differences in size. Until the identity could be confirmed, specimens from Texas were called Nylanderia species near pubens. Researchers at Texas A&M University did morphometric and DNA studies to help determine its identity, but results were inconclusive. In Trager's revision of Nylanderia for the continental United States (Trager, 1984), he mentioned records of N. pubens from Brownsville, TX collected in 1938, but remarked that is was incorrectly identified and was really N. fulva, a South American species. In fact, collections of N. fulva are also known from Chicago, IL from as early as 1931 (MEM collection records), but these records were based on indoor populations and likely no longer occur there. I also know of early records from Washington, D.C. These two species are both in the same group (N. fulva group) and are similar enough that Creighton (1950) synonymized them. Likewise, as recently as 2007, N. pubens was considered a synonym of N. fulva (Bolton et al. 2007). In Trager's revision (1984), he noted that the parameres of the male genitalia of N. pubens was bordered by a dense fringe of at least 30 blondish macrochaetae (see photo above); whereas, he stated that the paramere of N. fulva had "sparse pilosity of uneven length and orientation (see photo above) which in no way resembles the characteristic fringe of N. pubens." I borrowed specimens from Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, and examined them, along with specimens that I collected in Mississippi. I found that the macrochaetae on the male parameres closely matched Trager's description of N. fulva, rather than N. pubens, which meant, according to Trager 's concept of these species, that the species causing problems from Florida to Texas was actually N. fulva. Other evidence pointed to the conclusion that specimens found throughout the southern US were all the same species. However, with the names N. pubens being in common usage, I was reluctant to use the name N. fulva without definitive proof or DNA corroboration. With this ambiguity and the need for a defininte name, it was not long before corroboration was made. A molecular study by Zhao et al. (2012) demonstrated that specimens from Florida and Texas were a single species. Then, also using molecular data, Gotzek et al. (2012) determined that this species now common along the Gulf Coast region was, in fact, Nylanderia fulva. So, finally, problem solved–our common crazy ant in the Southeast is Nylanderia fulva. History of Occurrence in MS: We first noted N. fulva in Mississippi in early fall of 2009. Dr. Blake Layton (MSU extension entomologist) and I visited an infested site in Hancock County after we received samples from the site that I confirmed as crazy ants. We were amazed by the incredible numbers of ants present at the site (which was roughly a square mile). The homeowners had tried repeated applications of various pesticides with no visible results. In addition to the obvious nuisance quality they presented, the ants also caused physical damage to a camper in which their colonies had forced the outer metal wall to bulge outward, to insulation of which the ants chewed through leaving powder behind, and some electrical boxes, which were shorted out. The winter of 2009-2010 proved to be quite cold on the Mississippi coast and several sub-freezing nights negatively impacted plants (such as palms). We were curious if the cold weather also affected the crazy ant populations, so Dr. Layton and I made a return trip to the site in March of 2010. The ants were not as obvious and abundant as during our previous trip, which was heartening. However, we found colonies of the ants under bark of pine stumps and in rotting pine logs, where they had apparently overwintered. High abundance of this species was again observed at this locality during a trip back to the area in June, 2011. In addition to the populations in Hancock County, we found this species at multiple localities in southern Jackson County in late 2010. We made a visit to that area in June 2011 and found abundance to be at a high levels. Through communication with extension agents and PCO's in the region during subsequent years, we have observed that localized populations have continued to grow and isolated new populations are popping up here and there. Currently, this species is found in all three of our coastal counties: Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson. We have noted that from year to year, existing populations along our Gulf Coast region are increasing in size, but that populations are localized, rather than widespread in the area. About the Common Name: The common name of N. fulva is the "tawny crazy ant", although it has also been called the hairy crazy ant, Caribbean crazy ant in Florida and the Caribbean region and in TX it has been called the "Rasberry crazy ant", named after Tom Rasberry, the pest control operator who "first" discovered them in that state. I put first in quotes, between, obviously, this species was already known from Texas from specimens collected in 1938 in Brownsville. However, Mr. Rasberry was instrumental in making the public and national media aware of the invasive nature of this ant (albeit, he was calling it the wrong name). These other common names are actually for the species N. pubens, not N. fulva. Thus, the new common name of "tawny crazy ant" was adopted for N. fulva to avoid confusion. Taxonomic History (provided by Barry Bolton, 2013) Diagnosis Identification Queen: Larger than workers (TL ≈ 4.0 mm, HL 0.95–0.96 mm, HW 0.96–0.98 mm, SL 1.03–1.04 mm, EL 0.35–0.37 mm, MeSL 1.64–1.65 mm) (n=2) (MEM specimens). Head and body brown to reddish brown, antennae and legs often lifer orangish brown. Head about as wide as long, widest posteriorly; posterior border straight; entire with dense, appressed, short setae, with scattered longer, erect setae; eyes large, about 1/3 the length of the head, located laterally along the midline; three ocelli present; mandibles with 6 distinct teeth; antennae 12-segmented, lacking a club, scapes long, lacking stout, erect setae. Mesosoma enlarged and with four wings or wing scars; dorsum flattened; entire mesosoma with dense, appressed, short pubescence; numerous, erect erect setae present dorsally; propodeum unarmed. Waist single-segmented, petiolar node mostly shiny. Gaster overhangs petiolar node; with dense, appressed, short pubescence, and numerous longer erect setae; acidopore present at the apex. Male: Small, about the same size as workers (TL ≈ 2.4–2.7 mm, HL 0.60–0.66 mm, HW 0.50–0.54 mm, SL 0.77–0.80 mm, EL 0.27–0.30 mm, MeSL 1.02–1.08 mm). (n=5) (MEM specimens). Orangish brown to reddish-brown. Head slightly longer than wide, somewhat circular; with numerous appressed, setae curving toward midline; several erect, stout, black macrochaetae present, especially posteriorly; eyes very large, about ½ the length of head, located on lower portion of head; three large ocelli present; mandibles with a slight notch at the apex forming one tooth followed by a long edentate section; antennae 13-segmented, lacking a club, scapes very long. Mesosoma slightly convex in lateral view; pronotum trapezoidal, slightly convex anteriorly; mesoscutum rounded anteriorly; propodeum angled about 45°; entire mesosoma with dense, short pubescence and scattered erect macrochaetae dorsally. Wings transparent yellow gray; forewing with closed costal, basal, subbasal, marginal and submarginal cells; pterostigma present hindwing with closed basal cell. Waist single-segmented, petiolar node thickened basally, rounded triangular, shiny. Gaster overhangs petiolar node; entire gaster with dense, short, appressed pubescence and numerous longer, erect setae; genitalia external with well-developed triangular parameres; parameres with elongate, flexuous setae of uneven lengths and orientation. Biology Food Resources: Tawny crazy ant workers tend various sucking hemipterous insects (aphids, mealybugs, scale insects, treehoppers, whiteflies, etc.) for honeydew (a sugary liquid extracted from plant hosts), which is excreted from the plant hosts. They are also attracted to plant nectaries, damaged or overripe fruit, and other sweet food sources. They supplement their diets with arthropods and small vertebrates for protein (Drees 2009, MacGown and Layton 2010, Meyers 2008a). We have observed this species tending Membracidae in Hancock County, MS (see photo above). Economic Importance Effects on Plants and Animals: Tawny crazy ants may reduce biodiversity of other animals, both invertebrate and vertebrate. LeBrun et al. (2013) reported that tree-nesting birds and other small animals have been forced to move out of areas inhabited by large populations of crazy ants. Wetterer and Keularts (2008) reported that large numbers of N. pubens workers caused deaths of caged rabbits in St. Croix. In Colombia, N. fulva is considered a serious pest that has displaced native fauna; caused chickens to die of asphyxia; attacked larger animals, such as cattle, around the eyes, nasal fossae and hooves; and caused grassland habitats to dry out as a result of elevated hemipteran levels on plants (Arcila et al. 2002, Meyers 2009; and personal comm. Paul Nestor, Texas A&M). Another exotic ant species, Pheidole obscurithorax Naves, from South America, which has much lower population levels than the tawny crazy ant, has been documented to attack hatchling chickens in Mississippi (Hill 2006). Large levels of the tawny crazy ant could be detrimental to the poultry industry in Mississippi if left unchecked. At high densities, this species shows potential to be an important agricultural pest due to its enhancement of phloem-feeding hemipterous insects that it tends (Wetterer and Keularts 2008). This species has been blamed for crop damages due to high numbers of plant feeding Hemiptera in St. Croix (Pagad 2011). Effects on tree health from increased levels of sap-feeding hemipterans tended by ants remains largely unstudied in this species. High densities of scale insects tended by the related yellow crazy ant, Anoplolepis gracilipes (Smith), have been reported to weaken trees and cause canopy dieback and/or death of trees from a sooty mold in the honeydew produced by the scale insects (Matthews 2004). Tawny crazy ants have been reported to destroy honey bee hives in Texas by consuming brood, and then colonizing the hive (Drees, 2009, Harmon 2009). Their presence in various materials being transported (i.e. hay, mulch, potted plants, etc.) may reduce value of goods (Drees 2009). Electrical Problems due to Crazy Ants: It is unclear whether Tawny crazy ants are attracted to electricity or if they are simply utilizing spaces associated with electrical equipment as nesting areas. Regardless, this species is often associated with electrical short circuits, which could potentially be dangerous in the right situation, and expensive in any situation. Large accumulations of tawny crazy ants have been reported to cause short circuits and to clog switching mechanisms, which has resulted in electrical shortages in a wide variety of equipment such as breaker boxes, electrical outlets, phone lines, air conditioning units, chemical-pipe valves, computers, security systems, cars, sewage lift pump stations, electrical systems in automotive vehicles, and numerous other (Drees 2009, Pagad 2011, Meyers 2008b). Control Due to the excessively large populations, this species is difficult, if not impossible, to control by a homeowner, and typically requires regular visits by professional exterminators. Even then, its difficult to keep this pest at bay when large populations are present. Because populations can become huge, often spreading through neighborhoods or into wooded areas surrounding homes, primary efforts should be concentrated on keeping the ants away from the home itself and from areas of high use. Ideally, in residential areas, a neighborhood approach should be used with all homeowners working together with area PCO's to control this species. However, due to pesticide restrictions, ants typically are able to reinfest an area from adjacent semi wooded to wooded areas or along wetland areas that cannot be treated with pesticides. Persistence is key. Drifts of Dead Ants Pest Status Distribution Neotropical: Anguilla, Argentina, Bermuda, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, St. Vincent & the Grenadines (Lesser Antilles), Virgin Islands (USA), (MacGown 2011, Trager 1984, Pagad 2011, Wetterer and Keularts 2008). US Distribution Florida: Alachua, Bay, Brevard, Broward, Clay, Collier, DeSoto, Duval, Hardee, Hillsborough, Indian River, Lake, Lee, Levy, Manatee, Marion, Martin, Miami-Dade, Nassau, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, Pasco, Pinellas, Polk, Saint Johns, Saint Lucie, and Sarasota Counties (Calibeo and Oi 2011, Deyrup et al., 2000; Klotz et al., 1995, Warner and Scheffrahn 2010, Pers. Comm. Dawn Calibeo-University of Florida and David Oi, USDA-ARS, Gainesville, FL). Illinois: Chicago (MEM; this is a historic record based on specimens collected by M. Talbot in 1931. This was likely an isolated indoor population that is no longer present). Mississippi: Hancock, Harrison, Jackson, and Pearl River Counties (MacGown 2011 and MEM records). Georgia: Brooks, Camden, Chatham, Dougherty, Glynn, and Lowndes Counties (MEM and UGA records). Louisiana: Ascension, Beauregard, Calcasieu, East Baton Rouge, Iberia, Iberville, Lafayette, Lafourche, Livingston, Morehouse, Orleans, Plaquemines, Rapides, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. Martin, St. Mary, St. Tammany, Terrabonne, Vernon, Vermilion, Washington, and West Baton Rouge Parishes, (Carlton 2014, Carlton and Bayless 2013, Hooper-Bui et al. 2010, Morgan 2011, Ring 2014. and Pers. Comm. David Oi, USDA-ARS, Gainesville, FL). Texas: Angelina, Bexar, Brazoria, Brazos, Cameron, Chambers, Colorado, Comal, Fayette, Fort Bend, Galveston, Hardin, Harris, Hays, Hidalgo, Jasper, Jefferson, Jim Hogg, Liberty, Matagorda, Montgomery, Nueces, Orange, Polk, San Augustine, Travis, Victoria, Walker, Wharton, and Williamson Counties (Anonymous 2014, Gold 2011, Meyers 2008a,b, Meyers 2009, and Pers. Comm. David Oi, USDA-ARS, Gainesville, FL).

Distribution Map of Nylanderia fulva in the US (updated May 2017)

|

||