Introduction

Ants in this genus differ from other ponerine ants found in the United States by the unique head shape; peculiar mandibles, which are elongate and inserted near the center of the clypeus (see photo above); the large tapering petiole; and the large size of the workers (for a more detailed diagnosis of the genus, see MacGown et al. 2014). Members of this genus are commonly called trap-jaw ants due to their elongate mandibles, which can be opened to 180°, then snapped rapidly together on prey. These ants are amazing in their ability to control and time the mandibular movement. When necessary, an ant can forcibly close the mandibles against a surface or other organism and actually propel itself away for up to several inches! Remarkable behavior. Additionally, they can use the mandibles for much more sensitive movements such as caring for larvae or nest building.

This species may be the only native Odontomachus species found along the Gulf Coast, except for O. clarus, which was recently discovered in Louisiana (Adams et al. 2010).

Taxonomic History (from Barry Bolton, 2012)

Described by Patton from Georgia

in 1894 as Atta brunnea; Emery moved it to Odontomachus and made it a junior synonym of O. insularis (1895); Brown later revived it from synonymy (1976).

Identification

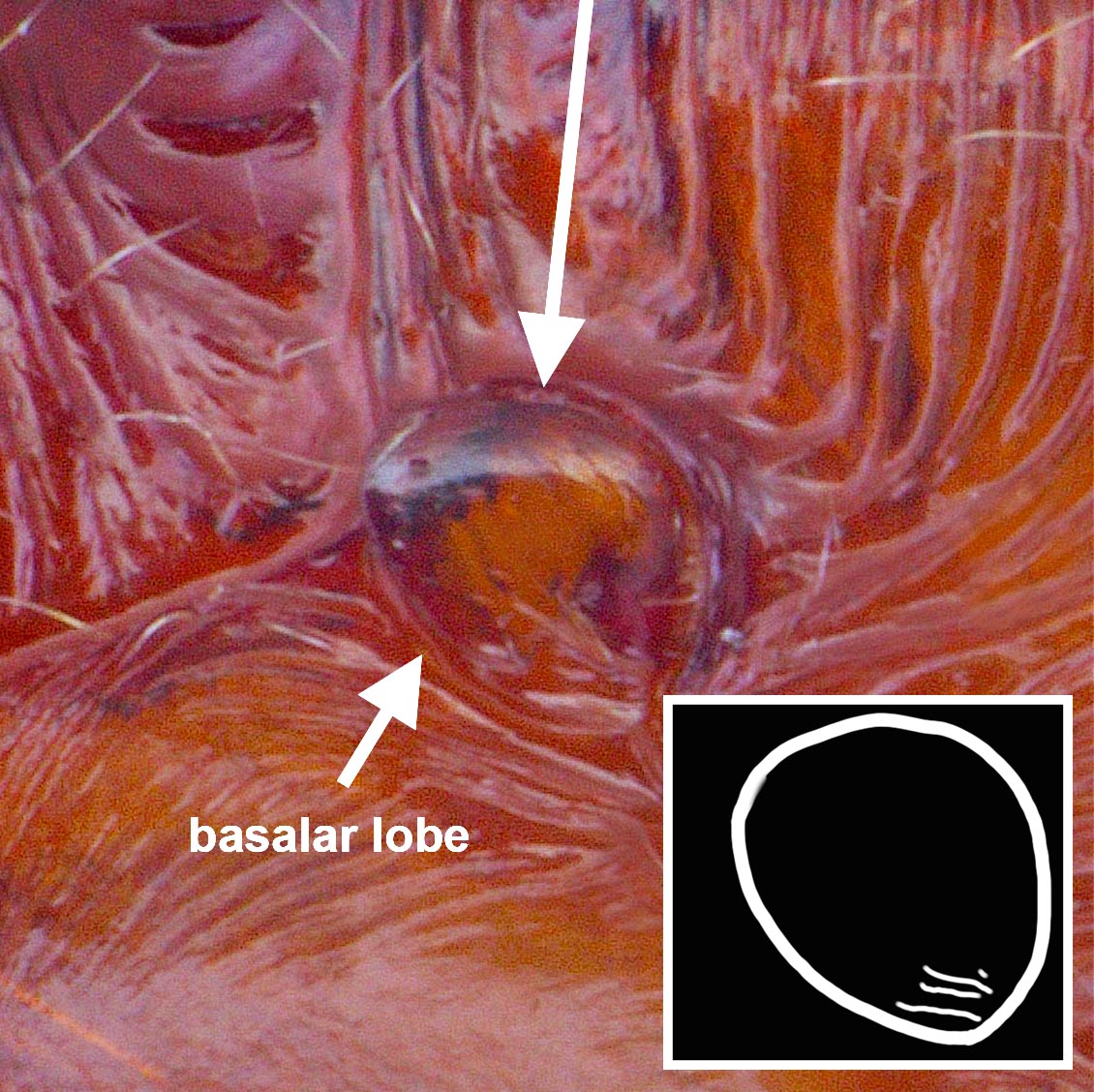

Worker: HL 2.10–2.44, HW 1.58–1.92, SL 1.84–2.10, EL 0.34–0.42, ML 1.16–1.36, WL 2.44–3.00, PTH 0.96–1.20, PTL 0.48–0.52 (n=10). Entire body generally shiny except where obscured by dense pubescence; head, mesosoma, and petiole dark reddish-brown to dark brown; gaster darker brown; scape and legs brown. Head with fine, longitudinal striae covering much of the head in full-face view, striae beginning from frontal lobes and diverging toward posterior corners of head, fading at corners and sides; sides and underside of head lacking sculpture; dorsally with numerous, fine, appressed pubescence and scattered elongate, erect setae present. Pronotum with sub-circular, concentric striae that become longitudinal near rear margin; pubescence appressed, abundant; 5–8 elongate, erect setae present. Mesonotum and propodeum with deep transverse striae; propleuron, mesopleuron, and basalar lobe lacking sculpture; pubescence abundant dorsally, appressed. Metasternum lacking paired, elongate, spiniform processes between hind coxae. Petiole widest at base, gradually tapering apically to a short spine directed rearward; mostly lacking striae with only faint striae present near base; subpetiolar process rounded triangular; appressed pubescence present anteriorly and laterally, but mostly absent posteriorly. Gaster mostly shiny beneath pubescence, lacking striae or other strong sculpture, but with fine coriaceous sculpture (seen at high magnification); fine, appressed pubescence dense, spaces between hairs less than 1/3 the length of a hair, often overlapping one another; scattered erect, elongate setae present.

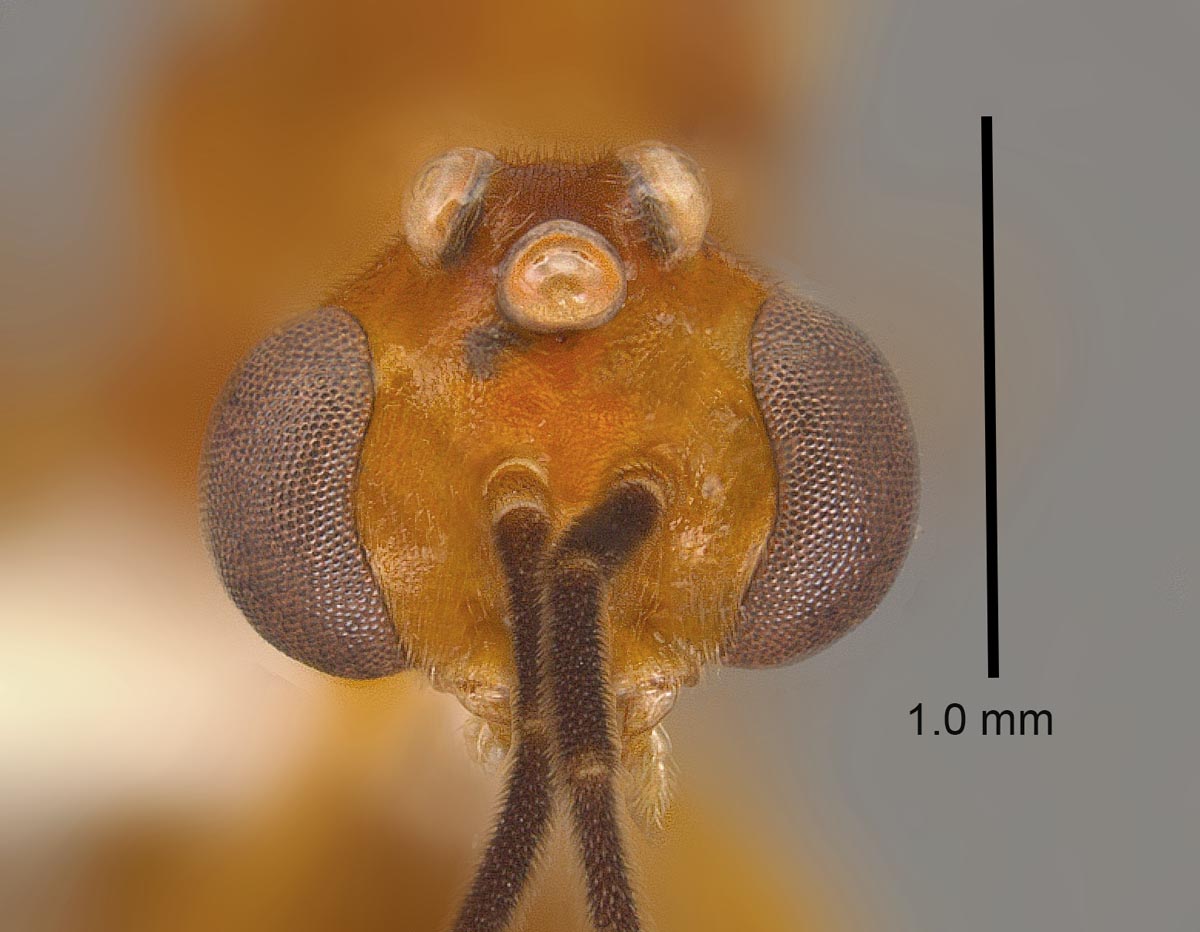

Male: HL 1.00–1.08, HW 1.24–1.34, SL 0.18–0.22, EL 0.68–0.76, EW 0.40–0.44, OL 0.24, OES 0.16, WL 2.52–2.76, PTH 0.72–0.88, PTL 0.46–0.54, FWL 5.10–5.65 (n=5). Head, mesosoma, and petiole generally shiny except where obscured by dense pubescence; head, meso- and metasoma, legs, scape and pedicel yellow to yellowish-brown, remainder of funiculus brown. Head and mesosoma with abundant fine, white pubescence except on anepisternum where pubescence is mostly absent. Eyes extremely large, maximum diameter of each eye at least 70% of the length of the head in full-face view. Ocelli large, the length of each ocellus wider than distance between lateral ocellus and eye margin; in full-face view, lateral ocelli protrude beyond posterior border of head. Mesosoma: pronotum lacking sculpture; mesoscutum with fine transversely arcuate striae anteriorly, striae becoming longitudinal posteriorly; mesoscutellum raised and convex, lacking sculpture; propodeum with weak to moderately strong transverse striae laterally, and especially posterodorsally; mesopleuron mostly lacking striae. Petiole bluntly rounded apically, with rounded triangular subpetiolar process anteriorly; densely pubescent anteriorly and laterally, but reduced pubescence posteriorly.

Queen: No specimens measured, but similar to workers in color and general appearance except slightly larger, with mesosoma developed for wings.

Diagnosis: Workers of this species are distinguished from others in our region by the much finer and denser pubescence on the first gastral tergite. Males are yellow-colored and most easily confused with those of O. haematodus;those of O. brunneus are clearly separated by the following characters: 1) ocelli larger, projecting beyond the posterior border of the head; 2) metasternal processes short, not elongate and spine-like; 3) posterior face of propodeum not offset from dorsal and lateral faces by distinct carina, and by numerous genitalic characters. Male O. brunneus are further separated from other US species by the transverse mesoscutal striae, and by the anteroposteriorly slender mesosoma.

Biology and Economic Importance

Odontomachus brunneus appears to be restricted to the southeastern US. Previous records of O. brunneus from the Caribbean, and Central and South America (Brown 1976) all appear to be of O. ruginodis. The situation was clarified by Deyrup et al. (1985) who recognized the distinction between O. ruginodis and O. brunneus and revived the former from synonymy with the latter. Brown’s statement (1976) that “O. brunneus”is well adapted to “marginal habitats” is consistent with the ecology of O. ruginodis, whereas O. brunneus in the Southeast is generally found in undisturbed natural habitats.

In the US, O. brunneus occurs in a wide variety of natural habitats including flatwoods, mesic forests, pine savannas, swamp forests, oak-pine scrub, upland scrub, sandhills, bayheads, edges of seasonal ponds, and elevated tussocks. Nests of O. brunneus have been found in leaf litter, rotting logs, at tree bases, and in open to partially covered sandy areas. Nest architecture has been explored and discussed by Cerquera and Tschinkel (2010). Workers occasionally forage during the day, but are more active at night. Upon colony disturbance, workers are not aggressive, but instead quickly retreat or vacate the nest. This is in sharp contrast to the aggressive defensive stinging behavior of O. haematodus. Alates have been collected from May through December. This broad time frame for alate activity contrasts sharply with the early summer activity of O. haematodus.

Distribution

Because species in this genus have been often misidentified, the distribution of this species is not clearly understood at this time. However, in the US, it is clearly only found in the Southeast: AL (Baldwin and Houston Counties), FL (Alachua, Baker, Bay, Bradford, Broward, Citrus, Clay, Collier, Columbia, Dade, De Soto, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Glades, Hamilton, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Martin, Monroe, Nassau, Okeechobee, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Sarasota, St. Lucie, Sumter, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, and Walton Counties), and GA (Clinch County).

Literature Cited

Adams, B. J., X. Chen, and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2010. Odontomachus clarus Roger (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Reported in Kisatchie National Forest, Louisiana. Midsouth Entomologist 3: 104-105. [Available online: http://midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu/pdfs/Vol3_2/Vol3_2_006.pdf]

Bolton, B. 2012. Bolton World Catalog Ants. accessed on October 2012. [Available online: http://www.antweb.org/world.jsp]

Brown, W. L., Jr. 1976. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section A. Introduction, subtribal characters. Genus Odontomachus. Studia Entomol. 19:67-171.

Cerquera, L.M & Tschinkel, W.R. (2010). The nest architecture of the ant Odontomachus brunneus. Journal of Insect Science 10, 1–12.

Deyrup, M. and S. Cover. 2004. A new species of Odontomachus ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from inland ridges of Florida, with a key to Odontomachus of the United States. Florida Entomologist 87: 136-144.

Deyrup, M., J. Trager, N. Carlin 1985. The genus Odontomachus in the southeastern United States (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News 96:188-195.

Emery, C. 1895d. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 8:257-360.

MacGown, J. A., B. Boudinot, M. Deyrup, and D. M. Sorger. 2014. A review of the Nearctic Odontomachus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ponerinae) with a treatment of the males. Zootaxa 3802 (4):515–552.

Patton, W. H. 1894. Habits of the leaping-ant of southern Georgia. American Naturalist 28:618-619.

Links

AntWeb Images