Introduction

Tapinoma species can be found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions of the world with some species found in temperate regions as well. Currently there are 74 identified species. They can be found nesting in a variety of different locations including, snady soil, rocky soil, dead wood, plant material, or pretty much anywhere that has a cavity that can contain a colony. Tapinoma species have also been observed to have a preference for sweet foods and can often be found tending honeydew producing insects.

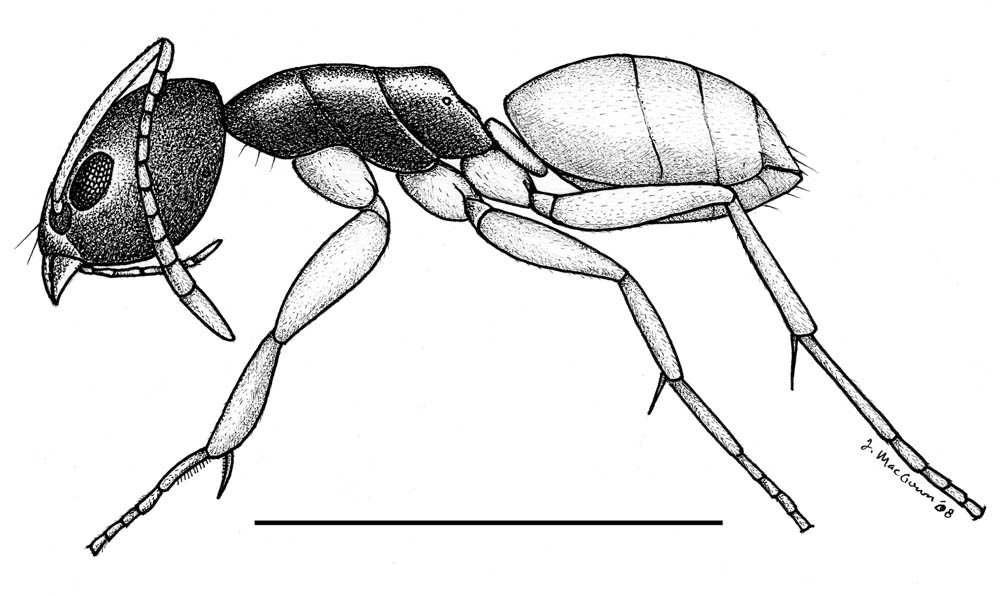

Tapinoma species can be identified by their one-segmented waist without a distinct node, lack of sting or acidopore, lack or erect setae on the mesosoma and only having four gastral tergites visible in the dorsal view.

Tapinoma melanocephum (Fabricius), commonly called the ghost ant, is an exotic tramp species thought to have originated in either the Afro tropical or Oriental regions (Smith, 1965). The ghost ant is considered to be a nuisance species that invades houses and businesses where it may nest and get into food stores. Workers of this species can be difficult to spot because of their coloration.

Taxonomic History (provided by Barry Bolton, 2016)

Formica melanocephala Fabricius, 1793: 353 (w.) FRENCH GUIANA. Neotropic. Emery, 1887: 249 (m.); Forel, 1891: 102 (q.); Wheeler & Wheeler, 1951: 197 (l.); Crozier, 1970: 119 (k.). Combination in Micromyrma: Roger, 1862: 258; in Tapinoma: Mayr, 1862: 651; in Tapinoma (Micromyrma): Santschi, 1928: 475. Senior synonym of Tapinoma pellucida: Mayr, 1886: 359; of Tapinoma nana: Emery, 1892: 166; of Tapinoma familiaris: Forel, 1899: 101; of Tapinoma australis: Wilson & Taylor, 1967: 80; of Tapinoma australe: Bolton, 1995: 401. Current subspecies: nominal plus Tapinoma melanocephalum coronatum, Tapinoma melanocephalum malesianum. See also: Smith, 1979: 1421; Shattuck, 1994: 148

Diagnosis

Ghost ant workers can be easily identified by their extremely small size and coloration. Workers are monomorphic and are only 1.3 to 1.5 mm in total length. They are bicolored with the head and mesosoma being dark brown to blackish brown and the appendages, petiole, and gaster being milky white. They have 12-segmented antennae, lack spines, lack a stinger, lack large erect hairs on the body, and lack a protruding node on the petiole. The petiole is often hidden by the gaster, which may overlap it. These minute ants are difficult to spot because of their size and partial light coloration.

Identification

Worker: Minute (HL 0.43-0.47mm, HW 0.39-0.40mm, SL 0.40-0.44, EL 0.11-0.12mm MeSL 0.46-0.50mm) (n=5) (MEM specimens). Bicolored with the head and mesosoma dark brown to blackish-brown and the mandibles, antennae, legs, and gaster a pale yellowish-white. Head roughly rectangular with fine, dense pubescence and a few erect setae on the clypeus; eyes located on the anterior half of the head; antennae are 12-segmented without a distinct club; scape extends beyond the posterior border of head; mandibles with three to four large teeth at the apex followed by minute dentition; long labial palps. Mesosoma with dense pubescence; dorsal surface divided into three sections by two distinct sutures; lacking any distinct sculpturing. Waist one-segmented, without a distinct node; often hidden by the overhanging gaster. Gaster with dense pubescence and a few erect setae on the fourth tergite; in the dorsal view four tergites are visible; sting lacking.

Queen: HL 0.56mm, HW 0.53mm, SL 0.50mm, EL 0.19mm, MeSL 0.83mm (n=1) (MEM specimen). Less distinctly bicolored than the worker with a brown head, light to pale brown mesosoma, and brown gaster with pale stripes at the posterior ends of the tergites. The mandibles, antennae and legs are all pale in color. Head with dense pubescence with a few erect setae on the clypeus; eyes situated slightly in front of the midline of the head; smaller ocelli present; conspicuous labial palps; 12-segmented antennae without a distinct club; scapes just reaching or exceeding the occipital border. Mesosoma with dense pubescence; elongated with the dorsal surface of the mesonotum flat; four wings or wing scars present. Waist is one-segmented without an obvious node; often hidden by the overhanging gaster. Gaster with dense pubescence and erect setae present on the last tergite; only four tergites visible in the dorsal view.

Male: (no MEM specimens)

Biology

Tapinoma melanocephalum is opportunistic nester that utilizes almost any cavity of sufficient size to house a colony. Nests may be found in disturbed areas, plant pots, under objects on the ground, under bark, at the bases of palm fronds, or other similar situations (Nickerson and Bloomcamp, 2006). Colony size ranges from small to large, and are often polygynous (Smith 1965). Relocation of colonies is not uncommon. New colonies may form when a queen and some workers leave a colony for a new suitable nesting site. Mating flights for this species have not been observed (Smith 1965). Tapinoma melanocephalum is attracted to sugars and has been observed to tend honeydew producing insects, as well as feeding on dead and live insects insects (Smith 1965).

Pest Status

Tapinoma melanocephalum’s ability to form colonies in any suitable crevice has led to them being a common house infesting ant. It has been reported to form colonies in wall voids in buildings and in potted plants (Nickerson and Bloomcamp, 2006). Fowler et al. (1993) and Moreira et al. (2005) reported that T. melanocephalum was the most common ant found in Brazilian hospitals with Moreira et al. (2005) finding at least 14 different types on bacteria on this species. Tapinoma melanocephalum was reported by Smith (1965) to forage indoors for sweets and other household foods. Longino (2006) reported that “weather you are in Guinea, New Guinea, or Guyana, if you are sitting at a table with a sugar dispenser you are likely to see workers of T. melanocephalum running about on the surface.

Distribution

Native Range: Unknown, possibly African or Oriental Regions (Smith, 1965)

Australian: Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hawaii, New Caledonia, New Guinea, Niue, Norfolk Island, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna Islands (antwiki.org).

Ethiopian: Cameroon, Comoros, Europa Island, Guinea, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mayotte, Oman, Reunion, Seychelles, Saint Helena, Senegal, United Arab Emirates, Yemen (antweb.org and antwiki.org).

Nearctic: Baja California, Canada, United States (antwiki.org).

Neotropical: Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, French Guiana (type locality), Galapagos Islands, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Lesser Antilles, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago (antweb.org and antwiki.org).

Oriental: Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bangladesh, Borneo, Cambodia, Christmas island, India, Indonesia, Krakatau Islands, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand (antwiki.org).

Palearctic: Afghanistan, Austria, Belgium, Canary Islands, Cape Verde, China, Finland, France, Hungary, Iberian Peninsula, Japan, Macaronesia, Netherlands, Republic of Korea, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Spain, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (antweb.org and antwiki.org).

U.S. Distribution: AL, AZ, CA, CN, FL, GA, HI, IA, KS,, IL, LA, ME,MI, MN, MS, MO, NC,NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, SC, TX, VA, WA, WI, and Washington DC, (MEM, antweb.org and antwiki.org, Wetterer 2009) [records from northern states are likely from indoor populations]

Southeastern U.S. Distribution: AL, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC (MEM)

Due to its spread by commerce, it is now widespread in subtropical and tropical regions. In the U.S. it is only known to be established in outdoor conditions in Florida, Hawaii, southern Texas, and most recently it has been discovered in outdoor situations in southern Mississippi (MacGown and Hill, 2009). Additionally, it has been reported in heated buildings or greenhouses in some northern states and even in Canada.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the ant work being done by the MEM in Alabama and Mississippi is from several sources including the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, under Project No. MIS-012040, the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station at Mississippi State University, with support from State Project MIS-311080, NSF Grants BSR-9024810 and DFB-9200856, the Tombigbee National Forest (U.S. Forest Service), the Noxubee Wildlife Refuge, Mississippi Natural Heritage Program Research Grant, USDA Forest Service Agreement No. 08-99-07-CCS-010, the William H. Cross Expedition Fund, and primarily by the USDA-ARS Areawide Management of Imported Fire Ant Project (2001-2014) and USDA-ARS Areawide Management Invasive Ants Project. Additionally, special cooperation has been provided by State Parks, National Forests, National Wildlife Refuges, the Natchez Trace Parkway, and from various private landowners in both Alabama and Mississippi.

Literature Cited

Bolton, B. 1995. A new general catalogue of the ants of the world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 504 pp.

Bolton, B. 2016. Bolton World Catalog Ants. Available online: http://www.antweb.org/world.jsp. Accessed 12 March 2016.

Crozier, R. H. 1970. Karyotypes of twenty-one ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with reviews of the known ant karyotypes. Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology 12:109-128.

Emery, C. 1887 ("1886"). Catalogo delle formiche esistenti nelle collezioni del Museo Civico di Genova. Parte terza. Formiche della regione Indo-Malese e dell'Australia. [part]. Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale 24[=(2)4]:209-240.

Emery, C. 1892 ("1891"). Note sinonimiche sulle formiche. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 23:159-167.

Fabricius, J. C. 1793. Entomologia systematica emendata et aucta. Secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, adjectis synonimis, locis observationibus, descriptionibus. Tome 2. Hafniae [= Copenhagen]: C. G. Proft, 519 pp.

Forel, A. 1891. Les Formicides. [part]. In: Grandidier, A. 1891. Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar. Volume XX. Histoire naturelle des Hyménoptères. Deuxième partie (28e fascicule). Paris: Hachette et Cie, v + 237 pp.

Forel, A. 1899. Formicidae. [part]. Biologia-Americana Hymenoptera 3:81-104.

Fowler, H.G., O.C. Bueno, T. Sadatsune, A.C. Montelli. 1993. Ants as potential vectors of pathogens in Brazil hospitals in the United State of São Paulo, Brazil. Insect Science and its Application 14, 367-70.

Longino, J.T. 2006. Ants of Costa Rica. http://academic.evergreen.edu/projects/ants/AntsofCostaRica.html, accessed on 7 April 2016.

MacGown, J. A. and J. G. Hill. 2009. Tapinoma melanocephalum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a new exotic ant in Mississippi. Mississippi Academy of Sciences 54: 172-174. [pdf]

Mayr, G. 1862. Myrmecologische Studien. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 12:649-776.

Mayr, G. 1886. Notizen über die Formiciden-Sammlung des British Museum in London. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 36:353-368.

Moreira, D.D.O., V. Morias, O. Viera-da-Mota, A.E.C. Campos-Farinha, A. Tonhasca-Jr. 2005. Ants as carriers of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospitals. Neotropical Entomology 34, 999-1006.

Nickerson, J. C. and C. L. Bloomcamp. August 2006. Featured Creatures: Tapinoma melanocephalum (Fabricius) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/urban/ants/ghost_ant.htm Accessed 5 May 2008.

Roger, J. 1862. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Ameisenfauna der Mittelmeerländer. II. Berliner Entomologische Zeitschrift 6:255-262.

Santschi, F. 1928. Nouvelles fourmis d'Australie. Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles 56:465-483.

Shattuck, S. O. 1994. Taxonomic catalog of the ant subfamilies Aneuretinae and Dolichoderinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). University of California Publications in Entomology 112:i-xix, 1-241.

Smith, M. R. 1965. House-infesting ants of the Eastern United States, their recognition, biology, and economic importance. United States Department of Agriculture, Technical Bulletin No. 1326: i-105

Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V.; Hurd, P. D.; Smith, D. R.; Burks, B. D. (eds.) 1979. Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. i-xvi, 1199-2209.

Wetterer J. K. 2009. Worldwide spread of the ghost ant, Tapinoma melanocephalum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 12:23–33.

Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1951. The ant larvae of the subfamily Dolichoderinae. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 53:169-210.

Wilson, E. O.; Taylor, R. W. 1967. The ants of Polynesia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Pacific Insects Monograph 14:1-109.

Links

AntWeb

AntCat

AntWiki

Discover Life ImagesFeatured Creatures-Tapinoma melonocephalum- http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/urban/ants/ghost_ant.htm Center for Urban & Structural Entomology, Texas A&M-Ghost Ant,Tapinoma melonocephalum- http://urbanentomology.tamu.edu/ants/ghost.cfm

|